- Home

- Sanjeev Shetty

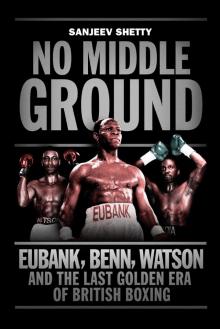

No Middle Ground Page 9

No Middle Ground Read online

Page 9

After returning from care hardly at all changed, Eubank lived on the streets, having alienated his father. It was around this time that he began running with a gang that specialised in stealing expensive designer clothing, some of which he’d sell, some of which he’d keep and wear. His daily income, he remembers, was generally in excess of £100 a day, quite a lot of money for the early 1980s. He would eventually get caught attempting to steal six suits but then, having avoided a custodial sentence, Eubank, ever the opportunist, escaped to New York, with his mother wondering what she could do to tame this most unruly of children. The hope was that now, away from his street friends, the impressionable Eubank would find something to channel his energies into. No one could have guessed what that would be; this was a sixteen-year-old who had only so far indicated a fondness for a lifestyle that he had shown no inclination to work for.

Boxing was in the family. Peter Eubanks was a talented featherweight who would inflict the first defeat of Barry McGuigan’s career on the Irishman. Young brother Chris says his motivation to enter a gym was to get fit but, almost certainly, the chip on the shoulder that developed after frequently having to fight his corner as the youngest sibling added to Eubank needing to find a way to prove he was the equal of his brothers. Just being a boxer wasn’t enough – he had to be one who stood out. As he admits, he lacked the natural ability of a great fighter so therefore focused on becoming a showman.

He stood out in a New York gym because of his accent. By now, the voice that would become as well known as any other aspect of him had changed. Honed by hours of listening to the BBC’s World Service, he had manufactured an accent and delivery at odds with anything you’d hear in one of boxing’s toughest gyms. Such was the impression he left that British journalists who visit his part of New York are still asked to this day whether they know the man who strutted around their gym thirty years ago.

Dennis Cruz was a super featherweight boxer who would eventually retire after a thirty-one-fight career which saw him fight a handful of world-class opponents. Although a southpaw, it was his style that Eubank attempted to imitate. Cruz was a legend of that New York gym, even if his career became a case of what if. According to Eubank, Cruz had more poise than any fighter he had ever seen but lacked the discipline, something the British man learned from. All the while, Eubank was sparring hard in the gym – legend has it that quite a lot of the best fights in New York take place in those tear-ups when the cameras aren’t on and the only spectators are gym rats. Having taken blows from his big brothers all his life, Eubank’s innate toughness would earn him respect then, as it did throughout his career.

Even so, Eubank would be stopped by a body punch in his first amateur fight. After that, there would be twenty-five more unpaid contests, six of which he’d lose, the other eighteen victories, culminating in his winning the light middleweight Spanish Golden Gloves title. There is a glory associated with accomplishment in amateur boxing which can rarely be replaced – in general, the endeavours of those involved in amateur boxing are more honest and linked to a love of ‘the sweet science’. But in the 1980s it offered no financial reward. Having already established a taste for the finer things in life, Eubank knew a successful professional career was the only way forward. Atlantic City was the venue on 3 October 1985, not long after Eubank had turned nineteen. American Tim Brown was the opponent and Eubank would win a decision after four rounds. He was paid $350 for the fight against an opponent who would fight only one more time. There would be four more bouts in Atlantic City – Eubank would go the distance against all of them, with the best victory over Eric Holland, a stocky Washington middleweight who would lose thirty-three of his fifty-nine contests but always guaranteed the paying public they would see a decent fight. It was Holland’s debut and he was knocked down for the first and only time of his career.

Eubank already had his unique selling point – he’d jump from the ring apron over the ropes, something he’d do for all but his last fight. As Steve Farhood remembers, ‘Eubank had presence, even then.’ If that remained a constant throughout his career, so did something else. ‘He was occasionally in non-action fights,’ added Farhood, who commentated on some of those early fights, broadcast on SportsChannel America. Eubank’s style was primarily that of a counter puncher – he’d rarely make the first move in any contest, preferring instead to respond to what his opponent would do. During those early years in America, he’d work with a number of trainers, picking up knowledge from all of them. But his primary influence came from his interest in the martial arts. He’d watched and learned from tapes of the great martial artists the ability to keep his distance from an opponent and how to get out of trouble, something he’d need both in the ring and on the rough streets of New York, where he frequently found himself in life-threatening situations. It is a style that is impossible to copy – and not many have tried to. Some, like future featherweight world champion Prince Naseem Hamed, have tried to claim credit for influencing a man eight years his senior. In fact, television footage from one of Eubank’s later fights in London show a young Naseem, at ringside, watching in awe the man in the ring holding himself in a way which was like nothing ever seen in a British ring. Those early bouts in America and his initiation in the gyms, where sparring was tougher than one might find in Britain, did much to build the toughness in Eubank, just as it had done to Benn. Surprisingly, Watson, the one fighter of the three whose style most resembled an American boxer, never based himself in the States for any period of time.

The problem with Eubank’s particular style was that it had technical flaws. Despite his insistence that he trained as hard as anyone, Eubank was essentially stubborn and hard to change. A case in point is footage of him working out with former undisputed world heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis after both had retired. In the video, Lewis looks stunned at the way Eubank jabs, from distance and leaning in with his body. When Lewis points out that he can jab from closer in, Eubank tells him that he ‘can’t pivot’. Within seconds, Lewis teaches Eubank how to do just that. The advice, coming from someone who achieved more than any British heavyweight boxer, carries enough weight for Eubank to be persuaded to listen, even if he would never put it to use in the ring. But finding anyone he thought worthy of listening to and learning from during his career was close to impossible.

Eubank’s five fights in America had taken him over fifteen months. He’d been combining fighting with studying but also admitted to missing his London family, specifically his brothers. On returning to England, Eubank slipped into the old habits – the shoplifting returned. The knowledge that there was no way for him to escape his past unless he returned to boxing meant he based himself in Brighton, where brothers Simon and Peter trained. It was there that he developed a friendship with Ronnie Davies, a former Southern Area lightweight champion who had become a trainer. Such was Eubank’s self-belief that he saw Davies as the man to protect him from the nasty side of the boxing business rather than the person who could transform him from fringe contender to champion. What worked so well about the relationship was that Davies knew his man was so strong-minded that interfering was not part of his agenda. ‘When you’ve got someone with that talent, you’ve got to step back.’

Eubank would hook up with a local promoter called Keith Miles and convince him to pay him a weekly wage so that he could give up the two jobs he had on the side, working at a fast-food restaurant and a department store. As a newcomer to the British scene, Eubank was not in position to go to a promoter and earn a contract which paid him enough to concentrate purely on boxing. Like many aspiring pugilists, he had to take other employment to make ends meet.

After nearly a year out of the ring, he returned with a one-round knockout over Darren Parker in Copthorne in Sussex. The following month, he’d beat perennial loser Winston Burnett over six rounds in the same county. More notable was the presence in the crowd of Karron Stephen-Martin, the woman Eubank would fall in love with a few months later.

Eubank retained his unbeaten

record over the course of the next twelve months, fighting frequently, most notably against former Benn foe Anthony Logan. While Benn had gone two life or death rounds with the Jamaican, Eubank, apart from a nervous moment in the opening stages, controlled the action and drew notable praise from boxing writers in England, who were starting to talk up the Brighton-based upstart. Eubank now had Benn on the brain. He understood the way self-promotion worked and calling Benn out was one way of getting people to notice him. At the time, Benn was the Commonwealth champion, awaiting a bout with Watson, and no one seriously believed Eubank was ready for such a fight or that he had the right connections for the bout to be made. What they and Eubank didn’t know was that the man who would soon become the most powerful player in the sport was on the prowl, looking for someone with the talent to spearhead his empire.

Barry Hearn, the qualified accountant, also had an eye for opportunity. In the 1970s, the east Londoner bought a snooker hall, just as the sport was starting to enjoy an unprecedented boom. Hearn began to manage players, most notably a painfully thin ginger-haired teenager, also from east London, called Steve Davis. It took Hearn five years to help Davis reach the summit of professional snooker, becoming world champion in 1981 for the first time. Davis would win another five. Plenty of other players followed into Hearn’s stable, impressed by how quickly Davis had become a celebrity. The likes of Ronnie O’Sullivan, Jimmy White and Dennis Taylor have all been managed by Hearn at one time or another.

Snooker wasn’t the limit of his ambitions: billing himself as a sports promoter, he’d also been involved in darts, football and boxing. His first foray was putting on Frank Bruno v Joe Bugner at White Hart Lane in 1987. That seized the attention of the establishment, but what was missing from his stable was a Davis, someone who you could gamble on, with the endgame being that person becoming world champion. Then he laid eyes on Eubank. Hearn was interested in the boxer, who was looking for representation.

‘I’d been watching him and saw his fight with Logan and was quite impressed. It was a tough fight to take. At the same time, I got a phone call from Len Ganley, the snooker referee, who told me there was a boxer who wanted to have a meeting with me,’ Hearn told me. ‘We arranged to meet at the Grosvenor House hotel in Sheffield during the world snooker championships. He swanned in, looking immaculate, as always. Beautiful tracksuit, swagger and his opening words to me were “Before we start, I have to tell you that I’m an athlete and I know my value”, so I thought, I like this. I’ve always liked characters in sport, I think they’re almost as important as ability, in terms of marketability. I was impressed with him and we did a deal.’ Eubank would be paid £1,200 a month for training expenses under the terms of the contract, which would only be renegotiated if he won a British, European or World title.

There are some relationships in boxing that just seem to work, even if the individuals involved seem slightly mismatched. Despite Muhammad Ali spending the vast majority of his career being represented by a radical black Muslim group, he retained a small white Italian American in the form of Angelo Dundee as his trainer, while Howard Bingham remains Ali’s personal photographer. Hearn’s East End patter seemed on the face of it to be diametrically opposed to the image of the Renaissance man cultivated by Eubank. But as brave as both might come across, either in the ring or in the negotiating room, both feared failure. Eubank had met most of the players in boxing by the time he sat down with Hearn. ‘He probably scared the likes of Maloney and Warren. They were pure boxing promoters, whereas I’ve always been a sports promoter. Boxing is a passion but I take a different view, in terms of my tolerance levels, which are a lot higher. I understand that geniuses are different people and we can’t expect them to be the same as us,’ says Hearn. Or, as one insider told me, Eubank was good for Hearn and Hearn was good for Eubank. Both saw the sport as a place where money could be made. Hearn’s involvement in snooker had shown him that for every player who won titles by being professional without being flash, like Steve Davis, for example, there was a need for the showman, like Jimmy White. In Eubank, Hearn thought he had another White, whose act was so unique it would draw in people who were perhaps ambivalent to the allure of the sport.

There would be disagreements between the pair as time passed but, mostly, they saw life in similar terms. One of the few during those early days was the terms of the contract. Eubank was after a retainer which would allow him to train without having to take a second job. He picked up £300 a week, which would help meet the cost of the child he and Karron would welcome into the world in September 1989 (Christopher Junior is now a ranked boxer), but there was another part of the contract with which Eubank wasn’t happy. Hearn insisted that the contract be voided if Eubank lost two fights. The boxer wanted that to be reduced to one, such was his belief that nothing could derail his career.

While Eubank would occasionally appear on ITV, the majority of his bouts were broadcast live on a fledgling satellite channel called Screensport, which showed boxing and golf. Hearn was happy to put most of his fights on that channel, even though he wasn’t earning huge sums of money from them. ‘Although I lost millions, and millions of pounds [in boxing], it set the business up,’ said Hearn. The immediate problem for Hearn was how to make that move from small shows to world title shows. During 1989 and then in 1990, there was little to suggest in the quality of opposition that Eubank faced that he was ready to fight someone of Benn’s calibre. Names like Hugo Corti, Frankie Moro and Jose Da Silva were unknown even to hardcore boxing fans, but at one of those bouts, against Kid Milo of the Midlands, Hearn brought along Trevor East, a producer and executive at ITV Sport. Hearn had given East the big sell about Eubank and, although there was not much in the way of action, East could see a personality, a presence, something a little different that could keep bums on seats when the TV came on.

Gym talk can fly around the world and can affect a boxer’s mindset – in 1989, even though Eubank was toiling at the intermediate level of the sport, he was telling everyone and anyone who would listen that he could beat Benn. By the time Benn had become world champion and Eubank was the holder of the spurious WBC International title, courtesy of his win over Corti, it was looking like a very outlandish claim. But it was having an effect. He’d told Boxing News in December 1988 that Benn was a ‘coward and a fraud’, words he would use to goad Benn for as long as it took to get him in the ring.

What helped him even more was the comment that has flown with Eubank everywhere he has gone. ‘Boxing is a mug’s game,’ he said in a magazine interview in 1990. Or that was how the quote was reported. In full, it read: ‘Boxing at a very low level/journeyman level is a mug’s game. Taking shots around the head for a pittance is without doubt a thankless task and a mug’s game.’ The majority in the sport heard or read the abbreviated version and took it as an insult. They had struggled to understand Eubank – ‘a boxer with an opinion,’ says Hearn – and this quote made up their minds for them. Here was a man biting the hand that fed him. He had also, in the minds of many, insulted the thousands of people who made their living from the sport, along with those who believed in boxing’s ability to turn young tearaways into men by installing a sense of discipline into their lives as well as teaching them how to act like men away from the gym. To this day, there are many who have still not forgiven Eubank for his comment. In the early 1990s, boxing in Britain wasn’t a sport you could casually be involved with. Generations of families were employed in the business, committed to the communities they worked in as much as they were to making a decent living from it. Only a select few made fortunes from it. They were the ones who felt hurt by Eubank’s comment, who could never forgive him for an apparent sound bite that belittled their endeavours. There were also boxers who had slugged away for years, taking and landing punches, accepting fights at a day’s notice and not getting paid what they hoped or expected, who could relate to Eubank.

What was immediately clear was that Eubank’s comment enhanced his reputation as a dilet

tante, someone so completely removed from the rest of the industry that he was now essential viewing. In the image-conscious twenty-first century, it is easy to believe that any self-respecting PR company would have apoplexy trying to limit the damage to their client’s reputation. Equally, many would have identified with Eubank’s position. How was it that so many boxers seemed to do all the work and yet ended up slurring their words and living off benefits, while their promoters sported none of those bruises and seemed to have endless amounts of cash? Eubank never spoke without thought, his utterances calculated to give the appearance of someone different from the crowd. He was convinced that people would pay to see him, whether because of his show or to see him lose. He’d preferred to be loved, but what he desired the most was respect.

On 25 April 1990, Eubank defended his WBC International middleweight title against Eduardo Contreras in Brighton in the kind of fight with which he would become synonymous – there was little in the way of action. It was on that evening that he first became acquainted with the ITV reporter Gary Newbon. The pair would develop a relationship which, over the years, would deliver televised exchanges more interesting than some of the fights under discussion. ‘You’ll never be world champion if you fight like that,’ Newbon told Eubank. ‘If that’s what your view is, you know nothing about boxing,’ the boxer replied. He had won a unanimous decision that convinced no one he could be a future world champion. The only people who still had belief were Eubank, and Hearn. That lack of credibility would suit the pair when it came to negotiating the big fight that they’d face at the end of the year – a challenge for the WBO middleweight title, now held by Nigel Benn. The returning hero might have been in America for most of the last eighteen months, but he knew all about Eubank and his mouth. Because the only fight Eubank wanted was Benn. Ever since he had beaten Logan, Eubank had been nagging away at Benn for a fight. Now that Benn had a world title, the goading became more intense. There were many things that set Eubank apart from other fighters and one of those was his certainty of who he could or could not beat. In 1989, he served as one of Herol Graham’s sparring partners as the Sheffield man prepared to fight Mike McCallum for the world middleweight title. Eubank contends that he spent a week chasing Graham round the ring, before finally landing a punch which floored ‘Bomber’. Graham says the first punch that Eubank threw put him on the canvas, after which the sparring sessions became so one-sided that Eubank left after a week, chastened by the knowledge that he had found someone more talented and complete than himself. ‘He was sick of me. We sparred for a week and at the weekend he went home. He needed a break because he couldn’t work me out. He didn’t know what I was doing or how I was doing it. He promised never ever to box me for a championship. And he was good to his word,’ says Graham.

No Middle Ground

No Middle Ground