- Home

- Sanjeev Shetty

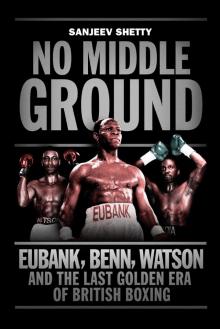

No Middle Ground

No Middle Ground Read online

SANJEEV SHETTY

NO MIDDLE

GROUND

EUBANK, BENN, WATSON

AND THE LAST GOLDEN ERA OF BRITISH BOXING

Contents

Introduction

Act I

Act II

Act III

Act IV

Act V

Act VI

Acknowledgements

Index

Copyright

For Mick Watts – I’ll keep writing them if you keep reading them

and

Richard Shepheard – it’s not Sonny Liston, but I hope it will do.

Introduction

It seems the easiest thing in the world to say, but they didn’t like each other.

If you were alive when Nigel Benn, Chris Eubank and Michael Watson attempted to settle things, you’ll know a bit about what it was like. And if you weren’t, then you have my sympathy. Because what we could not have realised then was how lucky we were. This was as good as it got and to quote my friend Glyn Leach, the editor of Boxing Monthly, ‘there’s been nothing to equal it since’.

It began under a tent, on a Sunday night, in a deserted part of north London and the scale of it all was summed up by where it finished. At the home of the English football champions, Old Trafford, with over 40,000 people crammed into a venue nicknamed ‘the Theatre of Dreams’, the unlucky ones without tickets were forced to watch it on television. If Saturday night square-screen viewing defines us as a nation, with the masses now drawn to the finales of Strictly Come Dancing and its ilk, then what did it say about us twenty years ago when we’d give up our evenings for blood, sweat and violence? Did we evolve, did boxing become less compelling or was it down to the quality of what was in front of us?

I’m not sure there are any easy answers to the question. Except that, when it reached its height, on that otherwise tranquil evening in Manchester, I was there, part of a quartet of people from contrasting backgrounds and diverging futures, united by one thing. We all had our favourites. One day, we’d all admit that if at times we wanted one of them to win more than the other, when it all came to an end, when the final punches had been thrown, admiring all three of them wasn’t a chore.

A two-man rivalry is essentially a pick-em. Him I like, him I don’t. When there are three, we look to find one who we can identify with. During the 1970s and early 1980s, one of sport’s most enduring rivalries could be found in tennis, with Björn Borg, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors locked into something that all of us could relate to. Borg was the full vessel, or so it seemed, a man so at ease it seemed impossible to ruffle his feathers, even when others tried. Connors was the artisan, the blue-collar worker who played every week because he’d known hard times and knew the value of every cent. And then there was McEnroe, the volatile, magical and charismatic kid who begged you to be seated even as he warmed up. Given his privileged background, no one could ever work out where the anger came from. But to see those eruptions was more than just a voyeuristic occasion. It was also a precursor to something that you knew would find its way into the scrapbooks.

While Borg, Connors and McEnroe were all-time greats, among the twenty best men ever to hold a racket, Benn, Eubank and Watson would probably only feature in the best-of category when the discussion turned to British boxers. However, the similarities were in how they felt about each other. There was dislike which quite often bordered on contempt. And these were young, angry men who had reached the ring by following different paths, but each of whom had a point to prove, and that made for a dangerous cocktail with a pair of ten-ounce gloves.

Chris Eubank looked imperious, his body seemingly carved from stone, his visage impassive and, whether by design or not, he dared his opponents to dislike him. Michael Watson had known hardship, raised with love but without luxury. He fought because it was something he was good at but also because he needed something other than faith and fresh air to live on. And then there was Nigel Benn, who could charm you outside the ring, but harm you inside it. The anger within was a mystery to those who didn’t know him. Even after years as a professional boxer, he didn’t know why he’d wake up and want to hurt people.

Born within two and a half years of each other, all of West Indian immigrant parents, and raised in London, their rivalries did not begin in the amateur ranks. It was only when they started to earn money that the dislike came to the fore. When they started fighting for financial reward, Britain was a haven for quick-buck artists. And when one of them made easy money, the other two were left wondering why their pockets were empty. They all wanted to be champions, but also wanted to be paid more than the other. They all sought independence from the men who managed their careers. And they all thought they were the best. Most attempts to settle things in the ring provoked more arguments.

Their contests sometimes reached genuine sporting greatness and at other times promised more than they delivered. But the tension was always there. These were three men who, at various times, genuinely despised each other – sometimes the hate appeared manufactured, but we didn’t know that, nor did we know how much that personal venom would both shape and destroy them. All we knew was that it made for some of the most unforgettable boxing this country has ever played host to.

In their own way, they’d all pay a high price for their endeavours. History tells us that ring wars, when fuelled by personal animosity, can have tragic consequences. In 2013 we mourned the passing of Emile Griffith, a superlative boxer of the 1960s, who spent the last fifty years of his life in a state of torment because of one of boxing’s most gruesome moments. Griffith, a humble welterweight from the Virgin Islands, became a popular figure in his adopted New York because of his classic style and easy-going attitude. In 1962, his demeanour was disturbed when an opponent, Cuban Benny Paret, grabbed his buttocks before a bout and called him a maricón, the day before they were due to fight at Madison Square Garden. The word maricón is Spanish slang for homosexual, something that no man would admit to being then and even less so if he was a boxer. It was the kind of thing one man could say to another in the 1960s without fear of the authorities interceding. Fast forward fifty years and the British heavyweight Tyson Fury can expect a fine from those who run the sport in this country for making homophobic comments on his Twitter account. Times have changed for the better, with even boxing, as old-fashioned a sport as any, doing more than before to eradicate prejudice.

But back to the 1960s, being called a maricón provoked a fury in Griffith which had not been evident before, perhaps because he had been harbouring doubts about his sexuality that he would struggle to come to terms with throughout his life. If those who managed and trained him regretted their fighter’s lack of anger, they had no idea of the consequences once that fuse was lit. Paret and Griffith had fought twice before, the Cuban winning the second bout after being stopped in the first. If only in terms of combat there had been honour in those bouts, there would be no such thing in the third and final episode of their rivalry. Griffith had been told by his trainer, Gil Clancy, to keep throwing punches if he got Paret in trouble. And in round twelve that’s exactly what he did. Paret, hurt in a corner of the ring, was subjected to an attack of unmistakable hostility and fury. More than twenty punches landed on his chin and upper body before he slumped to the canvas, unconscious. The images were captured live on American television and even the most optimistic viewer would have been able to tell that Paret’s life was in danger. The Cuban slipped into a coma from which he would never awake, dying nine days after taking his final punch. It was the first ring death ever recorded on live television and its memory still brings a shudder to those who saw it in the flesh or on celluloid. Boxing disappeared from television screens in America for ten years, so haunting w

ere those final seconds of Paret’s life. In the course of Benn, Eubank and Watson’s rivalry, there was a reminder of how close a boxer’s life comes to a premature end when the reason to fight becomes personal and not professional.

That kind of fury between fighters didn’t disappear because of one tragic bout. There would be countless other examples of men who didn’t care for each other and didn’t mind expressing it before, during or after battle. And, what’s more, that feeling, call it dislike, animosity, or just pure hatred, wasn’t discouraged. Gym gossip, the kind where one fighter lets a future opponent know by word of mouth that he wants to hurt him, continued. And promoters, sharks if you don’t like them, smart businessmen if you do, turned a blind eye when one of their boxers opened his mouth and uttered the kind of words he’d never use in front of his mother. They knew that a promotion lived or died on quality and hype. You didn’t need to manipulate the paying public when the match-ups were competitive and a belt was on the line, but if that wasn’t the case then throw in some personal animosity and old-fashioned contempt and you definitely had a full house.

The era of Eubank, Benn and Watson was a time when boxing’s place in the social landscape was much more prominent. Men had fought in what passed for a ring for centuries, long before football became this country’s obsession. Its appeal had not diminished as the twentieth century drew to a close, as virtually every boxer was subjected to the ‘Ali’ complex – how could any of them match up to the most charismatic athlete the world had ever seen or heard? They couldn’t, but ‘the Greatest’ had given them all the platform they craved. If his unique brand of braggadocio, bombast, beauty and brutality made him the most captivating boxer of any era, then those who followed suffered in comparison. Until it became apparent that you could market a fighter in different ways. In Britain, there’d be a Jim Watt, an Alan Minter, a Charlie Magri or a Maurice Hope. All of them world champions, but with qualities that were unique. Watt was durable, always finding ways to pull victory from the jaws of defeat. Minter was tough and tricky. Magri, with that flat nose, was everyone’s idea of what a fighter should be, and Hope’s silky skills were different from what we’d become accustomed to in British rings.

They’d come and go and there would be a period during the mid-1980s when Barry McGuigan’s star shone so brightly you’d have thought him capable of unifying Ireland, such was his stature. ‘The Clones Cyclone’, however, never quite dominated the way we thought he would, a combination of tragedy in and out of the ring robbing him and us of more excitement.

And then, from nowhere, came Benn, Eubank and Watson. Not one of them began with the fanfare that had accompanied the professional debut of amateur star Errol Christie, and their rivalry wasn’t something that you could predict. But as Benn began despatching what he called Mexican road sweepers, as Watson took the old-school route and beat some of America’s best veterans and Eubank breezed into England with an act both unique and inflammatory, they became a threesome as exciting and flammable as any we’d seen for years. And the story they told us was that they weren’t too keen on each other. Over the space of four years and five fights, there would be upsets, insults and tragedy. And it was hard to ignore. Whatever your background or sporting preference, you knew when a fight between any two of them was on. To see them live was a privilege but, if you couldn’t get a ticket, terrestrial television was the alternative. Living rooms around the country were nearly as hostile as the arenas and stadiums where the fights were taking place. Boxing, by its very nature, doesn’t encourage the half-hearted. You had to have a favourite. Was it the destructive force of Benn, who combined savagery with flash? His love of the good life and rags to riches tale resonated with those who believed that the best way to survive during the Thatcher era was to take your chances and maximise your income and profile. Or did you favour the hard work and honesty of Watson, who did things the old-fashioned way and rarely sought shortcuts? Never one to court publicity, he merely tried to be the best he could be and a vast percentage of this divided nation, who had seen Britain change so much during the 1980s, with huge swathes of working men rendered obsolete and unemployed, could relate to this humble Londoner who struggled to gain respect and adulation for just doing his job. And what about Eubank, whose eccentricities made him the boxer everyone wanted to hear from and who quite a few wanted to see lose. He’d become the darling of the chat shows, drawing a new breed of boxing fan to ringside – those who found preening and showboating as appealing as raw violence.

It seemed irrelevant that they were probably a level below the best at their weights. Eubank knew who he could beat and who he couldn’t and showed little desire to seek fights against the likes of James Toney or Roy Jones Junior, two American boxers who were contenders for boxing’s mythical title of best ‘pound for pound’ practitioner. Benn happily admitted he didn’t mind being number two to Jones, while Watson’s limitations were exposed the first time he fought for a world title. But these three Brits didn’t need to go abroad to make their names or money.

As ever, someone had to miss out. Herol Graham’s misfortune was to be born a decade earlier and also to be too good. If he’d been given the opportunities his talent deserved, there’s an argument to say I’d have no book to write. ‘He would have stood them all on their head,’ one ex-fighter told me.

In describing the period between 1989 and 1993 as the last great era of British boxing, it might seem I’m dismissing the thousands of men and women who have pulled on gloves in the twenty years since. It should not be construed as such. It’s recently been proposed that the calendar year of 2013 might be one of the best in the history of the sport. There have been top-quality skirmishes on these shores and elsewhere. Froch, Burns, Barker and Fury spring to mind, while the enigma that is Floyd Mayweather continues his journey towards recognition as one of the ten greatest fighters ever. I’ve watched them all, but the chances are the majority of you haven’t. That’s because in the twenty-first century, if you want to watch boxing on television, you have to pay. Your BSkyB subscription will get you only so far and then, after that, it’s a list of channels on which you need to see the best of the rest. Of the names I’ve mentioned, Fury is the only one you can still get with your licence fee. If he ever does fight for a world title, however, you can be certain you’ll need to pay a little extra to someone else.

I mention all this because the Herculean struggles between these three men, Benn, Watson and Eubank, were broadcast on television for a mass audience. And the timing of those bouts, on Saturday or Sunday night, meant they mattered, whether you liked it or not. So when one of these three won, it was a cause for celebration. And when something went wrong, it meant a degree of soul-searching and debate. When boxing was in the public eye, the morality of one man punching the other into a state of disarray and sometimes disability became a debate heard in the House of Commons. Its position now as a niche sport means that, if something similar happened today, an MP would have to ask for a tape of the fight before passing comment. Boxing has all but disappeared from free-to-air television. The biggest bouts are available only if you wish to pay extra. Both Benn and Eubank finished their careers on BSkyB, a fraction of the audience watching their last moments. Boxing can be found aplenty on satellite television in the 2010s and the die-hard fan has more choice than ever before. But it all costs. Old fans are prepared to pay but it’s hard to believe new fans are being attracted to a sport which is as old as any. It’s that exposure which made the Eubank, Benn and Watson era so special. Anyone and everyone could watch them. And the fights were so captivating and emotive that it competed in our consciences with the national sports of football and cricket. And during a period of our history when the Conservative government, led by Margaret Thatcher, divided the nation so spectacularly, the outlets for some of our woes and disagreements were the regular battles between these gladiators.

Act I

Scene I

The roads that boxers take, or are forced on, to stardom

and glory are both similar and yet different. For every young Cassius Clay who becomes Muhammad Ali after being the victim of theft (the young man from Louisville, Kentucky, was directed to a boxing gym by a policeman after expressing his anger at having his bike stolen), there is a Mike Tyson who learns fear and rage when one of his pigeons has its head ripped off by a fellow teenage delinquent. The paths are similar because, somewhere along the line, there is anger, rage, fear or a need for revenge, emotions that boys struggle to understand and therefore turn to fighting. The difference comes when those boys become men and begin to understand their emotions. Some control them and use boxing as a profession and also a form of expression. Others use the anger and pain as part of their fighting DNA. The fire inside them burns and burns; when allied to talent, it is a proposition difficult to stop but easy to sell.

As one of seven brothers, there didn’t seem anything exceptional about Nigel Benn, born on 22 January 1964, as he entered his ninth year. The second youngest of the brood, born to parents from Barbados who had immigrated to England, Benn had energy to burn and wasn’t opposed to a healthy scrap with his brothers. The exception to the rule was his relationship with his eldest brother, Andy, who had been born in the West Indies before coming to England to be reunited with his family. Nigel described his relationship with Andy as being ‘like a lion with his cub’. He idolised his big brother, who enjoyed a reputation as a genuine tough guy in the east London suburb of Ilford. To this day it’s not known whether it was that reputation or his own arrogance that led to Andy’s premature death. The bare facts are that he bled to death after falling from a house he should not have been in. According to Nigel Benn, the event was rarely discussed in the family household. Seventeen-year-old Andy Benn was buried in an unmarked grave, perhaps the biggest sign that none of his family knew how to react to his passing. It all left his eight-year-old brother with one overriding emotion.

No Middle Ground

No Middle Ground