- Home

- Sanjeev Shetty

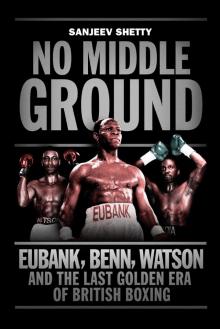

No Middle Ground Page 7

No Middle Ground Read online

Page 7

The harder questions would be directed at Benn. Could a man with the desire to be a world champion really devote so much time to his hair? Why was he spent after four rounds? And in a sport in which courage is measured in how much blood a man sheds on his way to the top, should a single jab have been enough to put him on the canvas and keep him there? More than a few boxing writers were of the opinion that he had ‘swallowed it’–in other words, had he quit? Was Benn yet another ogre who knew only how to bully and was redundant as soon as the man in the other corner blocked and punched back? Benn would cry many private tears before answering any of those questions.

Act II

Scene I

Michael Watson’s reward for beating Nigel Benn was a fight with the WBA middleweight champion Mike McCallum. Hardly a reward, but, post-Marvin Hagler, McCallum was as good as it got in the middleweight division. The Jamaican, now in his mid-thirties, had been fighting at world title level for five years and had beaten high-calibre boxers like Don Curry, Milton McCrory and Herol Graham. He had earned a reputation for being a particularly dangerous body puncher but there was also evidence that he was on the slide. He had been ‘outspeeded’ by Sumbu Kalambay and many felt he had been lucky to get the decision against Graham. No one felt that Watson was in for an easy night, but he would probably start marginal favourite.

Watson was now the mandatory challenger for McCallum’s belt and promoters were invited to bid to stage the fight. Mickey Duff had put on McCallum’s fight with Graham and it seemed obvious that he would win the right to promote a bout between the champion and his man Watson. What upset the applecart was the emergence of another promoter who was keen to get a piece of the action. Relatively new to the sport, Barry Hearn had spread his wings from snooker, where he had enjoyed great success with the likes of Steve Davis, to boxing. Hearn, who began life as an accountant, had promoted Frank Bruno’s win over Joe Bugner at Tottenham’s White Hart Lane in 1987 and, by the end of the 1980s, he was becoming a serious player in the sport, even though he lacked a world champion. Hearn’s offer to stage the bout was more lucrative than Duff’s. In winning the purse bid, Hearn established himself as part of the Watson camp and also increased the divisions between the fighter and his current promoter.

Watson had been convinced that Duff didn’t believe in him, especially for the Benn fight. In his book Twenty & Out, Duff denies this and says he made money out of betting on his man to beat Benn. Whether he believed in Watson’s talent as much as the fighter himself is another matter. Duff came from a different time and his grounding in the sport came during the 1950s and 1960s, where fighters would often have forty or fifty bouts before their first world title challenge. As far as he was concerned, he couldn’t see the need to rush. Watson, who was only twenty-four and had time on his side. He also didn’t want him to fight McCallum. He could see the problems for Watson against such a cagey fighter, who knew as much about boxing as Watson and had been a practitioner for so much longer. Duff didn’t think Watson would lose, but he would have been happier pursuing other, safer options. For Watson, Duff losing the purse bids for the fight was to prove a liberating experience.

If there had been joy for Watson in beating Benn, it was tempered by what followed immediately in the aftermath of the fight. The day after the win, his post-fight victory press conference was interrupted by Benn, who offered genuine praise to his conqueror before reminding those present that he would be back. If that irked Watson, it was nothing compared to seeing the former champion on television later that day admitting he had underestimated the challenger, had spent too much time on his hair but was now going to America to transform himself into the genuine article. He even had the nerve to say that, when he returned to England with a world title, he’d happily have a rematch. Watson’s moment was gone – a winner he may have been in the ring, but the PR battle was a no-contest. The papers wrote as much about the loser as they did the victor. The softly spoken man from north London was seething. How could his career still look tame in comparison with that of the man he had so comprehensively dismantled?

Whether or not Hearn knew of Watson’s dissatisfaction, he spoke the language the champion wanted to hear. Hearn spoke of future fights, which would include maybe another battle against Benn and also a bout with one of his stable. He had recently taken on another British middleweight who had been based in America before returning for home comfort. His name was Chris Eubank. At the time, mention of his name had little effect on Watson, who was focused purely on the world title challenge against McCallum. What Watson did notice was the way Hearn went about his business; while Duff was keen for his fighters to learn the business and pay their dues, Hearn saw boxing as business, where fights were made if people wanted to see them. ‘It’s a horrible, dirty, money-grabbing business … the one factor that binds it all together is money,’ Hearn told me. ‘We have fighters now that, as much as we love them, I will put them in against the devil himself with a bazooka gun, if the money is right. And they know that. And it’s better to be honest with them. I’ll say to them “Why did you start fighting? Did you start fighting because you wanted a belt on your mantelpiece in your council house or did you start fighting because you wanted the house on the hill? You started fighting because you wanted to change your life.”’

As the eighties drew to a close, with another recession about to hit and the threat of the poll tax looming, money was an increasingly important factor for men in such uncertain pursuits such as professional boxing. The best way for Watson to make that money, to provide for his two daughters, was to win a world title. Watson would not be the first or last boxer to enter Hearn’s offices in Essex and seek better recompense for his labours. While so many people seemed to be struggling to find the money to pay bills, Hearn, who had made a fortune through snooker, had the cash and connections to lure boxers into his stable. The bout would be in November 1989 at Alexandra Palace. Meanwhile, in America, his old adversary Benn was busy.

Benn had gone to Miami, where he would be trained by Englishman Vic Andretti, a former British light welterweight champion. Jettisoned was Brian Lynch, his apparent failure to come up with an alternative game plan against Watson making him an appropriate and easy scapegoat. It wouldn’t be the last time that Benn changed trainers. For now, he was immersed in boxing history – the 5th Street Gym, where he trained, had seen many of the greats go through their paces, Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard to name but two. Those two may have been famous for their ability to dance in the ring, but Benn’s initiation was more brutal. Whatever the truth about his dislike of sparring, in Miami he sparred and took his lessons the hard way. The ‘crash-bang-wallop’ style was replaced by a more patient approach, with the jab becoming a new and permanent feature. Andretti preached calm and Benn listened. Defeat had left him embarrassed to walk around London, where he feared those on the street might have thrown a few choice words in his direction. In Florida, he was no one. His children and partner, Sharron, remained in England, the theory being that distractions were harder to find in Miami. It had often been said in boxing circles that Benn’s style was better suited to American audiences, where aggression was prized above defensive genius. If Benn was to achieve as much as possible with his natural talent, the States was a suitable forum on a number of levels. He wouldn’t be reminded of what happened to him in Finsbury Park. He’d learn about his chosen sport from more experienced men and he could also, in theory, escape some of the distractions that life in London offered. However, life in Miami wasn’t exactly a case of solitary confinement.

He had friends with him, like hellraiser pal Ray Sullivan, or ‘Rolex Ray’, as he became known, and Mendy was never far from the action. The manager divided his time between the two sides of the Atlantic, doing deals to keep Benn’s profile high. On one occasion he returned to the States after reading in one of the national newspapers about a night of passion involving Benn and a local woman. The newspaper had, in graphic and intimate detail, told of how Benn had e

aten strawberries off her naked body. When confronted about it by Mendy, who was trying to placate his fighter’s partner, Benn not only admitted to the infidelity but also confirmed he had encouraged the girl to sell her story and make some money!

Benn’s extra-curricular activities might have hurt those back at home and been a hassle for those in charge of his career, but they never seemed to affect the fighter’s energy levels. He trained, as he had done in England, with a zeal and energy that bordered on the maniacal. Throughout his career, Benn would have disagreements with his trainers about the amount of sparring he’d need, but no cornerman ever had cause to reproach him for a lack of effort when preparing for a bout. In America, whether or not he’d been out the night before, Benn would always make his 6 a.m. run, which would range from six to twelve miles. In the 1990s, such burning of the candle at both ends wasn’t uncommon for top athletes – the Manchester United and England captain Bryan Robson was known as both a prodigious drinker and ferocious trainer. But Robson paid a price – he was injury-prone, failing to complete two World Cups while still in his prime. Benn would find years later that his hectic private life denied him a longer career.

Despite his first defeat, Benn wasn’t considered dead wood by some of the big players in American boxing. Bob Arum, whose organisation Top Rank had promoted several of Marvin Hagler’s bouts, liked the Englishman’s style and offered him a two-fight deal. ‘He was a charming guy,’ says Bruce Trampler, the firm’s matchmaker, who put Benn in with the tough Dominican Republic middleweight Jorge Amparo for the first of those bouts. The thirty-six-year-old didn’t punch hard enough to pose a threat, but he wasn’t the kind of opponent likely to fall after absorbing one punch. The fight, staged in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on 20 October, ended with Benn victorious after ten rounds. For the first time since he had turned professional, Benn had been forced to go the distance. While he proved that he possessed the stamina required and that maybe the exhaustion against Watson was an aberration, critics also wondered whether this proved Benn lacked the power at the highest level.

Five days later, his old amateur rival Rod Douglas had the biggest bout of his career. After thirteen consecutive victories, he was matched against Herol Graham, who went back to defending his British middleweight title after that loss to McCallum. Douglas was outclassed and then stopped after nine one-sided rounds. Shortly after the fight ended, Douglas suffered a blood clot and, although he would recover, the nature of his injuries meant he would never fight again. The doctor who cared for him was consultant neurologist Peter Hamlyn. It would not be the last time he’d treat a stricken boxer.

As Watson approached his first world title challenge, it seemed nothing could go wrong. He had not just reached the levels of fitness and conditioning which had proved Benn’s undoing, he had surpassed them. His chief sparring partner had been an old friend named Ray Webb, whose lanky frame made him ideal for the challenge posed by McCallum. Sparring is usually done until the week before the fight, in order to avoid injuries, but with eight days to go until the bout Watson sustained a broken nose, which forced an immediate cancellation. All the momentum that Watson had built after the Benn victory was lost. He had become, by virtue of that victory, the man to watch in the congested British middleweight scene. The setbacks he’d suffered before beating Benn had been put to one side and, with that, those feelings of envy and disillusionment also faded. But that training mishap made him question why things couldn’t always go his way. Watson knew that an extra five or six months to prepare for McCallum would be of little use. All the while, he’d know that the man he’d beaten so emphatically in his last fight had picked himself up and was causing a stir in America. This should be my time, thought Watson. But fate was conspiring against him.

Barry Hearn rescheduled the contest for April 1990. If Watson didn’t fight until then, he’d have spent nearly a year on the sidelines. Older fighters benefit from such a rest, their bodies needing time to heal, but Watson, who had had a relatively meagre twenty-three bouts in five years, needed the activity. He pleaded with both Hearn and Duff to get him a warm-up in the interim, but nothing could be arranged. This time, training was more of a slog, the sharpness that he had felt in 1989 replaced now by a feeling that he was treading water. To add further to his sense of disenchantment, Watson watched McCallum go twelve hard rounds with a young Irish fighter based in America called Steve Collins. That bout, which the champion won on points, took place two months before the rescheduled Watson fight. It was a double psychological blow for the Jamaican – it shook off the cobwebs and also sowed further seeds of doubt in the British boxer’s mind. ‘He should have had a couple of warm-ups,’ says Leonard Ballack, Watson’s longtime friend who could usually be seen at ringside.

Come 14 April at the Royal Albert Hall, Watson entered the ring not quite at the physical level he’d attained for much of the previous year. Even if the fight had taken place on the original date, he would have had his hands full against McCallum, but now, with a year of inactivity hampering his sharpness, it was a hard night for the challenger. Consistently beaten to the punch and outworked, Watson lost most of the first six to seven rounds. At that point, he put in one last effort, stepping in with harder punches. McCallum took them and marched on – in fifty-five fights, against some of the hardest punchers, ‘the Body Snatcher’ had never been knocked out – before reasserting his dominance, finally stopping an exhausted and discouraged Watson in the eleventh round. It was a beating that worried many who saw it – even Duff, who was being gently moved away from the apex of the Watson camp, implored his fighter to leave the middleweight division, so concerned was he at the scale of sacrifice being made. He’d watch Watson fail to draw a sweat after ten minutes of warming up before the bout and worried that his fluid intake after the weigh-in had been inexpert, leading to a dramatic loss of power and strength on the night. You can have all the perceived weapons you like in a boxing ring, but if the powder is damp before you’ve pulled the trigger it doesn’t matter what ammunition you’ve packed.

There was no disgrace in losing to McCallum, who would go down in history as one of the best of his era, but Watson was now back to where he had been before the Benn fight. To add further pressure, his relationships with key people, such as Zara, the mother of his two daughters, and Duff, were deteriorating. The scale of his defeat meant a return to domestic matters was the only way forward. Watson hadn’t done enough to deserve a rematch – McCallum had been tested more stringently by Collins. A victory for Watson would have been life-changing – a rematch with Benn would be worth at least three times as much with a world title at stake and there would surely have been more endorsements for becoming the country’s first middleweight world champion since Alan Minter in 1980. Watson dreamed of earning enough money to secure the future of his daughters and also the respect of the boxing world, and the journey to those goals was far from complete. As he convalesced, he knew, not for the first time in his career, that bigger challenges awaited.

In America, the Nigel Benn experiment was enjoying some success. Six weeks after going the distance with Amparo, ‘the Dark Destroyer’ – a nickname that was fully embraced in the States – stopped Puerto Rican Jose Quinones in one round in Las Vegas. The performance was a perfect combination of the old and new Benn. Hard punches, thrown correctly and sparingly, producing the knockout. Benn left the ring with reporters being told they’d just seen the ‘English Marvin Hagler’. In truth, the man Benn most aspired to be was Mike Tyson, at that time the undefeated and undisputed heavyweight champion of the world. The pair had met and Benn couldn’t help but admire Tyson. The money, the female attention and the power of his celebrity had an effect.

Back in England, the night before Benn beat Quinones, his former manager and promoter Frank Warren was shot in the chest, the target of an apparent assassination attempt by a masked man. Warren would make a full recovery and return to the sport he loved. Police charged Terry Marsh, a friend of Benn, and Warren’s fir

st world champion, with the attempted murder, but the retired boxer would eventually be acquitted. During Warren’s absence from the business, promoters like Hearn flourished. Young, promising fighters saw that Hearn had money to spend and signed with him, knowing they could expect better exposure as well as remuneration. But of more importance to Benn was the absence from his camp of Marsh, who had become invaluable as a source of mirth and encouragement. Despite his love of nightlife, Benn was naturally more comfortable in the company of friends and family.

Eight days before his twenty-sixth birthday, Benn would go the distance again, this time against American journeyman Sanderline Williams, who was a late substitute for compatriot Michael Olajide. The purpose of a proposed fight with Olajide – once again in Las Vegas – was to put Benn in a position to fight the legendary Roberto Durán for the WBC middleweight title. Neither fight transpired and, although Benn failed to shine against Williams, a slippery boxer who’d fight half a dozen world champions and never be stopped, fate was on his side. Bob Arum’s Top Rank signed him to a new five-fight deal worth a basic £250,000 per bout and then positioned him to take on the WBO middleweight champion Doug DeWitt. The WBO were not recognised as an official sanctioning body in the United Kingdom and therefore the challenger was happy once again to fight in someone else’s backyard. DeWitt looked to be all wrong for Benn, who had earned a reputation for toughness dating back to his days as Marvin Hagler’s sparring partner. He’d mixed in good company for most of his career and had won the title the previous year against Robbie Sims, Hagler’s half-brother. His experience and the fact that he’d fought better opponents for the majority of his career made him a strong favourite when the pair met on 29 April. Colin Hart of the Sun, who had tipped against Benn for the Watson fight, predicted another loss for the Englishman. Even Jim Rosenthal, who presented the coverage for ITV from New Jersey, says ‘we all thought he’d get battered’.

No Middle Ground

No Middle Ground