- Home

- Sanjeev Shetty

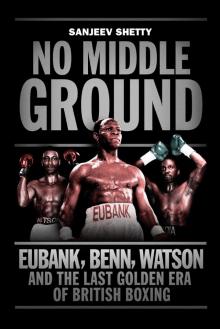

No Middle Ground Page 4

No Middle Ground Read online

Page 4

In the modern era, such a result for a young, undefeated fighter might have constituted a disaster, but Watson took it as a positive. He had become overconfident, seemingly unaware of his athletic mortality. In his previous seven fights, his size and strength, allied with solid boxing fundamentals, had been more than enough to see him through. Now he realised there was another level he had to go to. The day after the bout, his pride wounded more than his body, Watson began training again, secure in the knowledge that his promoter was still with him but aware that the fan base he had built up during his victories had dwindled and would only return when he hit the big time.

He’d fight again in November 1986, a routine points victory over Alan Baptiste at Wembley. The following year would see Watson have five bouts, the opposition consisting of some of Britain‘s better journeymen. Cliff Gilpin, Ralph Smiley and Ian Chantler were boxers you could learn things from – although Chantler would become another footnote in Benn’s career, lasting less than twenty seconds – and Watson continued his education without tripping up. By the end of 1987, Duff decided to up the level of Watson’s opponents, matching him with a series of tough American fighters. Don Lee was the first of those – he had already met Britain’s Tony Sibson, the tough Doug DeWitt and rising contender Michael Olajide. The Lee fight was shown on the BBC, and the venerable commentator Harry Carpenter remarked that some of Watson’s best work was ‘in the trenches, where American fighters are usually considered stronger’. The fight would end in the fifth round, stopped by the referee courtesy of a nasty cut on the American’s mouth. Lee showed no disappointment at the premature ending, having been outpunched and outboxed for the entire bout. At six feet two and fighting out of the southpaw stance, Lee should have presented more problems for Watson. That he didn’t said much for the British man’s knowledge of the basics of the sport and his revived sense of dedication, which had been missing from the Cook bout. Watson thinks Duff didn’t believe he could win the fight, one the boxer describes as one of his hardest.

Watson was also, like Benn, redefining the stereotypical image of the British boxer. For years, it was perceived, especially in America, that fighters on this side of the Atlantic preferred to box with a rigid, upright stance, chin high in the air with a jab pushed out in defence as much as offence. Watson worked from angles, in a crouch, unafraid of getting in close and using his strength to outmuscle his opponent. The wins began to build up in 1988 – Joe McKnight, Ricky Stackhouse and Kenny Styles all failed to hear the final bell, overpowered and outskilled by Watson, who would make his one and only foray into America that year, against Israel Cole. The fight was registered as a technical draw; stopped after one round because of a cut, under Nevada boxing rules – the fight took place in Las Vegas’s Caesars Palace – this meant an automatic draw. The year would end with a fight against another American, Reggie Miller, who had tested Benn twelve months earlier. There would be no problems for Watson in this fight, which lasted five rounds and was one-sided from start to finish.

Nineteen eighty-eight was the year that Watson’s potential started to take him places – but only in boxing circles. He was ranked in the top ten of the governing bodies, but his profile outside boxing remained minimal. Clive Bernath, editor of SecondsOut.com, one of the sport’s leading websites, says of Watson: ‘He was a bit of a throwback to the old days. He had good sparring with the rest of the Mickey Duff stable. But he was not box office.’ Mike Costello says, ‘Watson was a fighter’s fighter. He was no-nonsense, old-school.’ He was also starting to worry why it was the man from the east side of London, Nigel Benn, who was making the headlines. The kind of fan who’d read Boxing News would know just how good Watson was and the recognition he deserved, but in the 1980s, long before the age of self-generated, social media coverage, Watson’s only form of publicity was his promoter and it’s possible that Duff did not really believe in his fighter’s ability. And maybe Watson, who lived by the creed that being good should be enough, didn’t help himself. ‘He didn’t have much hype about him – he just worked hard and was very old-school. He didn’t boast or brag and therefore probably wasn’t as easy to market,’ says Boxing Monthly’s Glyn Leach. It would come as no surprise that Watson would one day go to Ambrose Mendy for advice on where to take his career, having watched ‘the Dark Destroyer’ gain a reputation for constant excitement and value for money, two qualities he believed he also possessed. Building up inside Watson now was a sense of both resentment and envy – how could he, for all his dedication, have acquired so little, while Benn, a man he considered inferior, was making such a splash? Watson knocked people out and punched hard. But, while Benn did it with a snarl, Watson seemed to approach his job with the precision of a surgeon. To the casual fan, Benn’s appeal was obvious: you wouldn’t have to wait too long for what you were really after – violence. With Watson, there was a sense that you needed to understand boxing’s scientifics a little better to really appreciate what he was doing.

As we have seen, at times Watson had taken a second job to supplement his boxing income – firstly in painting and decorating and then, latterly, as a minicab driver. He also had a family to support, a girlfriend, Zara, and two daughters. It all added up to a situation where he needed a moment to show the world how good he was and also get paid what he thought he was worth. Following two routine wins at the start of 1989, Watson, in a rare moment of bravado, told reporters he could beat Benn, because of his ‘superior boxing ability’. Neither Duff nor his trainer, Eric Secombe, believed their man could do it, which gave Watson all the motivation he needed.

Watson could have continued fighting tough American middleweights for as long as he wanted, but they weren’t going to give him the paydays or recognition he felt he deserved. There was one man he thought he could beat; one man whose name resonated throughout the British Isles and even further abroad. Victory over him would finally put him closer to where he wanted to be. For Michael Watson money was one thing, respect another. But he dreamed of becoming a world champion, and victory over Nigel Benn would take him closer to realising that dream. Watson had respect for Benn and his punching power, but was growing increasingly annoyed at the attitude of the Commonwealth champion, who didn’t seem to rate him any higher than the calibre of opposition he’d been facing for the past eighteen months.

‘I haven’t got the recognition I deserve. I’ve been very underestimated. This is a great opportunity for me to go out there and box to my full potential,’ said Watson after learning that he’d fight Benn. In his mind, Watson could hear Mickey Duff telling reporters that if he lost to Benn he would not be ready for a world title fight. ‘This is a big break for me now – no one has really seen what I can do. Fair enough, people make a big thing about Nigel Benn, but let me tell you, Nigel Benn will be in for a painful experience and it will be an experience he’ll never forget. If I don’t get respect from Benn outside the ring, I’ll certainly get it inside.’ Behind the bravado and the braggadocio, the most telling thing Watson said was that he felt undervalued. After the Benn bout, he’d make moves to ensure he never felt like that again. But for now, he was merely a talented middleweight boxer, without a unique selling point – although he had by now acquired the nickname ‘the Force’ – and, more importantly, without a title. In the 1980s, there wasn’t the proliferation of belts now available to fighters. There were four world governing bodies, the WBA, WBC, IBF and the emerging WBO. To earn a chance to fight for one of those titles, a boxer generally needed to prove he was good. A win over Benn was that chance for Watson. Until he won or lost, he would have, as many people told me, a ‘chip on his shoulder’. In his mind, he knew he was the best, that he’d studied boxers and their techniques, copied the ones he thought most effective and refined all he’d learned into a smooth style. In Benn, he merely saw a straightforward brawler, a man without subtlety. Yet this boxing primitive had the money and limelight. Aggrieved and still exuding envy and resentment, Michael Watson could now also see clearly what he h

ad to do. Win.

Scene III

‘I’ll do him, I’ll smash him to pieces. I will do him – definitely,’ Benn told Ambrose Mendy shortly after meeting Watson for the first time at a stage-managed occasion at the Royal Albert Hall. ‘But Michael wasn’t scared,’ remembers Mendy. To put the fight together, Mendy, Frank Maloney and the lawyer Henri Brandman arranged a meeting with Mickey Duff at the Phoenix Apollo at Stratford in the East End. When the fighters’ representatives met, Duff refused to deal with Mendy.

‘You’re not a licence holder,’ Duff told Mendy. While Benn’s manager remained outside, negotiations began inside Duff’s favourite restaurant and a contract was signed at around two in the morning, with Duff having held court for most of that time. Maloney says he kept himself sober, because the sums of money involved were large for such a Commonwealth title fight. In the end, both parties agreed that their fighters would earn £100,000, with the bout set to take place on 21 May 1989.

At the time, Watson’s fitness was in part down to a friendship he had formed with another boxer who worked out at the same gym, a featherweight called Jim McDonnell, who is now regarded as one of the top trainers in British boxing. McDonnell’s lifelong commitment to keeping in shape means that even today, in his fifties, he regularly runs marathons inside three hours. Both men were facing the challenges of their lives that summer. Ten days after Watson’s fight against Benn, McDonnell would face Barry McGuigan, now making a comeback, in what was a crunch bout for both. If McGuigan lost, he’d almost certainly retire from the game for good, while a win for McDonnell, who’d start as underdog, would yield him a world title fight. Aside from each man facing a make or break challenge, both Watson and McDonnell were devoted Arsenal fans. And as the 1988–9 football season reached its climax, the Gunners went to Anfield, the home of champions and league leaders Liverpool, needing to win by two goals to secure their first title in nearly twenty years. Watson and McDonnell had a bet that both would win their bouts and their team would go to Liverpool on 26 May and win 2-0.

The football season was finishing later than usual that year because of an event which, only now, has finally received some semblance of an explanation. On 15 April 1989, ninety-six Liverpool fans lost their lives after being crushed at the Leppings Lane end of Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough stadium during an FA Cup semi-final between their team and Nottingham Forest. The match was abandoned with few aware of the scale of the tragedy. Liverpool’s understandable reluctance to consider playing another until their players felt ready meant a fixture backlog for the Merseysiders. But such was the low standing of football supporters in the 1980s that many regarded Hillsborough as a tragedy of supporter ignorance, and not, as was subsequently proved by an independent report commissioned by the Conservative government in 2012/13, the culmination of a series of serious mistakes made by the police, who allowed too many supporters into an end of the ground in which there was not enough space and where fences prevented a quick escape, and other emergency services who were too slow to respond when the situation escalated dramatically.

Football hooliganism had been a problem that had blighted the sport in Britain. Fences, introduced during the 1970s to prevent supporters invading the pitch, were indicative of the low esteem in which fans were held by the clubs they supported and the authorities. Skirmishes inside and outside grounds were on the rise during the 1980s and if that meant that the ordinary supporter, who went to football simply to watch some sport, was maligned, then so be it. Football, which had become the preserve of the working class after the Second World War, when tickets were affordable, and boys spent many a Saturday afternoon sitting with their fathers in old-fashioned and often unsafe stands or crammed into equally antiquated terraces, was no longer the ideal venue for a safe day out. And nothing was being done to change that. You could go to any league match without a ticket, in the knowledge that one could be purchased before a game without any proof of identity, and that increased the chances of an opportunistic thug entering a ground and starting trouble. Elements of hooliganism, whether organised or spontaneous, could be found at virtually every stadium in the country. And there were basic safety issues – in 1985, a fire started at Bradford’s Valley Parade stadium, destroying the main stand in less than a quarter of an hour and killing fifty-six supporters.

Neither did football have quite the number of stars that the Premier League would develop. The 1990 World Cup would make a household name of Paul Gascoigne, but he had to shed tears on a word stage before anyone really noticed him. It would not be until the start of the Premier League in 1992, backed by satellite television money and now family friendlier with the introduction of all-seater stadiums (introduced after the Taylor Report, following the Hillsborough disaster), that the sport began to find a new, more marketable identity.

It wasn’t that football left a void for boxing to fill; it was just that the latter fitted more comfortably into an era when the working man felt displaced. Safety at a boxing event wasn’t always paramount – promoter Frank Warren recalls a particularly brutal atmosphere at the Tony Sibson–Frank Tate fight in 1988 – but supporters making trouble at an event at which punching was legal was rarely as likely to make headlines in the way it did at football. Add that to the fact that boxing was almost always on television during the 1980s and you have a sport with a strikingly different outlook from the one you find in the modern era. While many bouts these days struggle to see the light of day because of problems about who will promote the contest and which television network will broadcast it, in 1989 there were considerably fewer such obstacles, certainly in the UK. There were only four TV channels – Channel 5 was a thing of the future – and two of those were owned by the BBC. Of the independent stations, Channel 4 had yet to show an interest in boxing, which left ITV as the logical home of the fight game. Apart from promotions by Frank Warren, the independent broadcaster would also be the place to watch top American fighters, including Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Sugar Ray Leonard and Thomas Hearns.

America’s love for the sport had dwindled during the eighties, in part because of one particular bout that ended in tragedy. In 1982, Ray Mancini, a very popular lightweight world champion, had knocked out a twenty-three-year-old South Korean boxer by the name of Duk Koo Kim in fourteen rounds. Four days after the bout, Kim died as a direct result of injuries he had suffered in the fight, which had been broadcast on terrestrial television. The World Boxing Council, under whose auspices the contest was fought, immediately ordered bouts to be shortened to twelve rounds. But the wider issue was the savage nature of the sport, which, according to longtime boxing writer Steve Farhood, meant boxing would appear on American television a lot less. The Tysons and Leonards would be seen on pay-per-view channels or closed-circuit television. An exception would be Benn–Watson.

Kevin Monaghan, then a leading executive at NBC, purchased rights to show the fight live on what would be a Sunday lunchtime slot in eastern America. The prime reason for the interest in the contest was Benn. ‘He had a distinct presence,’ says Farhood, who has edited The Ring magazine and has also commentated on boxing for television. ‘He was completely different from the kind of British fighter we had been used to seeing.’ Even given the quality of opposition Benn had faced, he’d caused a stir on the other side of the Atlantic, because of his ‘crash-bang-wallop’ style. The broadcasting of the Watson fight was the ultimate compliment. Commentating on the bout would be Dr Ferdie Pacheco, a familiar name to boxing fans as the man who had been Muhammad Ali’s physician.

If America’s interest in Benn was proof of his emerging power at the box office, it was the potency of his fists that most concerned Watson. ‘If I had my hands down, I knew he could knock me out in the first round,’ admits Watson now. The challenger was used to sparring with bigger men such as Dennis Andries. But in order to negate Benn’s advantage in the power stakes, Watson had to think of a strategy different from any he had employed in his previous bouts. Normally a boxer who liked t

o go forward, Watson would have to adapt a defensive posture. His plan had echoes of one of the sport’s most famous contests. In 1974, Ali had fought the hitherto undefeated wrecking machine, George Foreman, in Zaire, in a bout christened ‘the Rumble in the Jungle’. For a number of reasons, Ali was a massive underdog. He seemed past his prime and was facing, in Foreman, a man who had destroyed the likes of Joe Frazier and Ken Norton in such brief and brutal fashion that there were genuine fears for the health of Ali, by now one of sport’s most popular and admired figures. After an opening round during which he was happy to trade blows with the bigger and stronger Foreman, Ali retreated to the ropes, his hands and gloves protecting both sides of his head, allowing Foreman to target his lower abdomen. The younger man threw punch after punch at Ali, with limited success, until the eighth round, when, apparently exhausted, he was knocked to the floor by a short barrage of punches from ‘the Greatest’. The strategy became known as ‘rope-a-dope’, yet another chapter in the enduring legacy of Ali. In order to pull off a similar tactic, Watson would need Benn to play the bull to his matador and, so far, there had been no evidence to suggest the champion knew another way to fight except straight ahead.

No Middle Ground

No Middle Ground